By Shaykh Omar Subedar – Mathabah Foundation

Observing the Taräwëh prayer during the blessed nights of Ramaźhän is an extremely virtuous act. Many benefits have been enumerated in various hadëths regarding its observance. Amongst them is; whoever stands [in prayer during the nights of] Ramaźhän with ëmän and hope [in Allah’s reward], all his past sins will be forgiven. [Bukhäri: 2009]

It is important to note that a person shall only be entitled to the benefits mentioned in the hadëths when he performs the prescribed ritual completely and correctly. Incorrect and incomplete acts of worship are never rewarded by Allah.

Today the taräwëh prayer has become an extremely controversial and confusing matter for many Muslims throughout the world, particularly in respect to the number of its raka’ät. While many argue that it is 20 others are adamant that it is only 8 thus leaving the average Muslim confused. In order to determine which view is correct it is imperative that we analyze all the prophetic narrations related to this matter. However before exploring this avenue it is important to first resolve whether the taräwëh prayer and the tahajjud prayer are the same ritual or not because the argument over the number of its raka’ät really stem from this particular point.

The Difference between Taräwëh and Tahajjud

When conducting a basic study of the Qur’än and hadëth we find that both prayers are really separate rituals. The tahajjud prayer is a prayer that was prescribed for the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم and his followers in Sura Al Muzammil during the early days of Islam. At first they were required to stand in prayer for at least half the night. Allah instructed, “Arise [to pray] the night except for a little. Half of it or subtract from it a little. Or add to it and recite the Quran with measure.” [73:2-4]

However Allah later relieved the believers of this obligation and announced towards the end of the sura, “So recite what is easy [for you] of the Quran,” [73:20].

Ibn Kathër has interpreted this verse as; “Without any limitation of time. Rather you may stand [in prayer during the night] for whatever period of time is easy [for you].”

This shows that tahajjud was a prayer that was practiced in the early days of Islam during the Makkan period; an era in which the only obligation the Muslims had was to pray. This prayer was observed year-round and was not restricted to a particular month during the year.

Regarding the taräwëh prayer or the night prayer of Ramaźhän, this was introduced by the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم during the month of Ramaźhän after its fasts were made compulsory in the second year of the migration. This is confirmed through the following hadëth;

Abu Salmän narrated, “My father told me that Allah’s Messenger صلى الله عليه وسلم said, “Allah has made the fasts of Ramaźhän compulsory for you and I have introduced standing [in prayer throughout its nights] to you. So whoever keeps its fast and stands [in prayer] during its [night’s] with ëmän and anticipation of reward, he will exit his sins (i.e. be absolved of them) in a manner that he will resemble the day his mother gave birth to him.’” [Nasa’ië: 1603]

This hadëth clarifies that this prayer differs from the tahajjud prayer, which the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم and his companions’ رضى الله عنهم observed throughout the years prior to the compulsion of fasting.

The number of raka’ät for the taräwëh prayer

‘Ä’isha’s رضى الله عنها Hadëth

Today a growing number of Muslims are under the impression that the taräwëh prayer consists of only 8 raka’ät based on the following hadëth:

Abu Salama ibn Abdur Rahman reported that he asked ‘Ä’isha رضى الله عنها about the Messenger’s prayer during Ramaźhän. She explained, “Whether it was Ramaźhän or any other month, Allah’s Messenger صلى الله عليه وسلم would not pray more than eleven raka’ät. He would pray four [raka’ät] and do not ask about their beauty or length. Then he would pray four [raka’ät] and do not ask about their beauty or length. Then he would pray three [raka’ät of witr].” [Bukhäri: 2013]

This narration has been recorded by Imam Bukhäri in his Jäme’ Al Sahëh in the ‘Book of the Taräwëh Prayer’. It is for this reason many people have assumed that Imam Bukhari has attempted to establish the number of raka’ät for the taräwëh prayer through his hadëth. However was that really his motive? And does this hadëth refer to the taräwëh prayer that was observed by the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم? These questions can only be answered by a person who has studied Imam Bukhäri’s work and has thoroughly understood his methodology.

In his Jäme’, Imam Bukhäri establishes a title in the beginning of a chapter, in which he normally makes an assertion and then presents authentic hadëths to support it. It is due to this that scholars have stated, “The fiqh of Imam Bukhäri is found in his titles.” In short, if a person would like to truly understand why Imam Bukhäri has recorded a hadëth in a particular chapter of his book, he should check the title of that chapter.

‘Ä’isha’s رضى الله عنها aforementioned hadëth has been recorded in a chapter titled; The virtue of he who stands [in prayer during the nights of] Ramaźhän. From this very heading we understand that by no means has the Imam attempted to establish the number of raka’ät for the taräwëh prayer, as is generally assumed. Had this been the case he would have composed a suitable title for it just as he has done in Chapter 10 of the Book of Tahajjud. There he has titled the chapter, ‘How the prayer of the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم was and the number of [raka’ät] he prayed during the night’. In this particular chapter Imam Bukhäri has presented a total of four hadëths through which he establishes the number of raka’ät the Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم prayed in tahajjud.

One would then wonder as to what virtue the Imam has attempted to establish through the aforementioned hadëth. When carefully studying his work we find that this very hadëth has been recorded in the 16th chapter of ‘The Book of tahajjud’ under the heading ‘The Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم standing [in prayer] during the nights of Ramaźhän and (in) other months’. This clearly shows that the prayer discussed in ‘Ä’isha’s رضى الله عنها hadëth is the tahajjud prayer of our beloved Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم, which differs from the taräwëh prayer. Through this chapter the Imam has proved that the tahajjud prayer was observed year-round by the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم and that the number of its raka’ät was consistent.

By presenting this very hadëth in the ‘Book of the Taräwëh Prayer’, Imam Bukhäri has attempted to prove that the reward for the taräwëh prayer is equivalent to the reward of the tahajjud prayer. This is understood by the chapter’s title. This does not imply that the two prayers are the same as there are many good deeds that are equivalent to one another in reward however by no means are they considered to be the same ritual. For example the reward for sitting in the masjid and waiting for saläh is equivalent to the reward of being engaged in saläh, as the following hadëth points out;

“…So when he enters the masjid he will be in the state of saläh as long as saläh keeps him [from leaving the Masjid].” [Bukhäri: 477]

It is common knowledge that no one considers these two actions to be the same ritual.

An interesting point to note is that none of the authors of the Sihäh Sitta (The six authentic compilations of hadëth) have used this hadëth in reference to the taräwëh prayer.

- Imam Muslim has recorded this hadëth in his Sahëh, Book 6, Chapter 17; The night prayer and the number of the Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم raka’ät during the night…’ and not in Chapter 25; Exhorting [people] to stand in [prayer during the nights of] Ramaźhän and that [prayer] is [called the] Taräwëh [prayer].

- Imam Mälik has recorded it in his Mu’atta, Book 7, Chapter 2; The Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم[method of] praying in witr, and not in Book 6, Chapter 2; What has been recorded pertaining to standing [in prayer during the nights of] Ramaźhän.

- Imam Abu Däwōd has recorded it in his Sunan, Book 5, Chapter 26; The Night Prayer, and not in Book 6, Chapter 1; Standing [in prayer] during the [nights of the] month of Ramaźhän.

- Imam Tirmidhë has narrated this hadëth in his Jäme’, Book 2, Chapter 208; What has been recorded pertaining to the description of the Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم prayer at night’ and not in Book 6, Chapter 81; What has been narrated pertaining to standing [in prayer during the nights of] the month of Ramaźhän.

- Imam Nasa’ië has recorded it in his Sunan, Book 20, Chapter 36; Why witr is [observed] with three [raka’ät], and not in the Chapter 4 of the same section; Standing [in prayer during the nights of] the month of Ramaźhän.

In conclusion, none of these eminent scholars of hadëth have considered this narration to be connected with the taräwëh prayer. They have however unanimously considered it to be connected with the Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم tahajjud prayer. Hence this hadëth cannot be used to determine the number of raka’ät the Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم observed while praying taräwëh.

Jäbir’s رضى الله عنه Hadëth

Some people resort to the following hadëth to prove that the number of raka’ät for the taräwëh prayer is eight:

Jäbir ibn ‘Abdullah reported, “Ubay ibn Ka’b رضى الله عنه came to the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم and said, “O Allah’s Messenger صلى الله عليه وسلم something happened to me last night, in Ramaźhän.”

The Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم asked, “What happened, O Ubay?”

Ubay explained, “Some women in my house expressed, “We cannot recite the Qur’än, hence we shall pray behind you.” Subsequently I led them [in prayer] for eight raka’ät and then led the witr prayer.”

The Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم looked like he was happy and did not say anything.” [Ibn Hibbän: 2540]

They contend that this hadëth clearly displays the Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم consent over observing eight raka’ät of taräwëh. The problem with this hadëth however is that it is unauthentic. Isa ibn Järiah, the individual who reported this account from Jäbir, is a narrator who has been heavily criticized by many hadëth scholars and has been labeled as weak. Yaĥyä ibn Ma’een said about him, “His narrations are not strong,” and in another place he expressed, “He has many ‘Manäkeer’ (i.e. hadëths in which the narrator is unreliable and his reports contradict the narrations of authentic narrators).

Imam Nasa’ië, Abu Däwōd, ‘Uqaylë, Ibn ‘Adë and Ibn Jawzë have all rendered him weak. Imam Nasa’ië and Abu Däwōd have gone as far to say, “He is a Munkir Al Hadëth” (a term used to label narrators weak).

Ibn ‘Adë stated, “His narrations are insecure [from weakness].”[1]

One may argue that Ibn Hibbän has listed him in his book, ‘Al Thiqät – The authentic ones’ and has recorded his hadëth in his Sahëh (compilation of authentic narrations) therefore he must be reliable. The reality is that Ibn- Hibbän is renowned for being lenient in authenticating narrators as Sheikh Abdul Fattäh has written in his commentary of ‘Al Raf’ wa Al Takmël’. Hence his authentication will not be given any weight, especially when it contradicts the criticism issued by multiple scholars.

Ibn Abbäs’s رضى الله عنهما Hadëth

As for those who assert that the taräwëh prayer consists of 20 raka’ät, they cite the following hadëth:

Ibn Abbäs رضى الله عنهما reported, “The Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم would observe 20 raka’ät and witr during [the nights of] Ramaźhän. [Musannaf Ibn Abi Shaybah: Chapter 227 Hadëth no. 13]

Unfortunately this hadëth is also weak because of Ibrähëm ibn Uthmän being in its transmission chain. Yaĥyä ibn Ma’een has heavily criticized him and has labeled him as unreliable.

In conclusion, there is no authentic hadëth available that reports the exact number of raka’ät observed by the Prophet صلى الله عليه وسلم in the taräwëh prayer. Hence in such circumstances one must examine the actions of his loyal companions in order to obtain some guidance.

‘Umar’s رضى الله عنه Conduct

There are approximately six narrations that describe ‘Umar’s رضى الله عنه method of observing the taräwëh prayer. However before analyzing them all, it is important to be aware of the structure of their transmission in order to fully understand them from an authenticator’s standpoint.

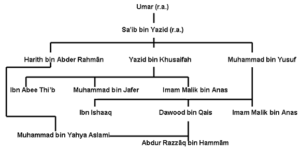

Firstly, ‘Umar’s رضى الله عنه practice has been reported by another Sahäbë named Sä’ib ibn Yazëd. Sä’ib reported his account to three of his students;

1) Härith ibn Abdur Rahman

2) Yazëd ibn Khusayfa

3) Muhammad ibn Yusuf

Yazëd ibn Khusayfa then reported this to three of his students

1) Ibn Abe Dhi’b

2) Muhammad ibn Ja’far

3) Imam Mälik ibn Anas

Muhammad ibn Yusuf reported this account to many of his students with variations in the number of raka’ät. Amongst them are;

1) Imam Mälik

2) Ibn Isĥäq

3) Däwōd ibn Qays.

Däwōd ibn Qays then reported it to Abdur Razzäq, the author of the famous ‘Al-Musannaf’. A diagram is given below to make all the lines of transmission clear;

Now that the entire transmission chain structure of Sä’ib ibn Yazëd’s reports are clear we go on to examine all his available reports one by one;

Now that the entire transmission chain structure of Sä’ib ibn Yazëd’s reports are clear we go on to examine all his available reports one by one;

- Mälik reported from Muhammad ibn Yusuf, who reported from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd who said, “`Umar ibn Al Khattäb instructed Ubay ibn Ka’b and Tamëm Al Dāri to lead people in prayer for eleven raka’ät. The reciter would recite the suras that consisted of 100 verses. Eventually we had to lean on canes due to the length of the prayer. We would only turn away from the prayer at the arrival of dawn. [Mu’atta Imam Mälik: 249]

Apparently this report is authentic because every narrator in its transmission chain is strong and reliable, however when analyzing the reports of Muhammad ibn Yusuf’s remaining students, we find that a total different story is being told. Häfiżh Ibn Hajar writes in Fat’h Al Bäri;

- “Muhammad ibn Nasr reported with a transmission chain leading to Muhammad ibn Is’häq, who stated, “Muhammad ibn Yusuf reported to me from his grandfather, Sä’ib ibn Yazëd who said, “During ‘Umar’s رضى الله عنه time we would pray 13 raka’ät in Ramaźhän.”

Ibn Is’häq said, “This is the most solid narration I have heard in connection to this matter. It coincides with ‘Ä’isha’s رضى الله عنها hadëth on the Prophet’s صلى الله عليه وسلم prayer during the night”

Here we find a clear contradiction between the two accounts. In the first narration Muhammad ibn Yusuf relates eleven raka’ät to Imam Mälik while in the second narration he reports thirteen raka’ät to Ibn Is’häq. Some scholars have attempted to reconcile the two reports by claiming that the additional two raka’ät reported by Ibn Is’häq are really the two raka’ät of the Fajr Sunna. This reconciliation can be deemed somewhat acceptable however the matter becomes problematic due to another narration;

- Abdur Razzäq reported from Däwōd ibn Qays and others, who have reported from Muhammad ibn Yusuf, who narrated from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd that ‘Umar رضى الله عنه gathered people during Ramaźhän [to pray taräwëh] behind Ubay ibn Ka’b and Tamëm Al Dāri for twenty one raka’ät. They would recite [suras that consisted of] one hundred verses and leave at the arrival of dawn.[Al Musannaf: 7730]

In this narration Muhammad ibn Yusuf narrated twenty one raka’ät to Däwōd ibn Qays and other students. Some scholars have attempted to discredit this account by presenting the following two arguments;

- It contradicts the previous report by trustworthy reporters of eleven raka’ät.

This, in reality, is an invalid argument. By studying the principles of hadëth we find that when a reporter’s account of a particular event contradicts other reports and every one of those reports are irreconcilable then they are all discarded and termed as Mudh’tarab. Here Muhammad ibn Yusuf has reported 11 raka’ät to Imam Mälik, 13 raka’ät to Ibn Is’häq and 21 to Däwōd ibn Qays. All their chains of transmission are authentic thus making it difficult to give preference to one report over the other. Therefore, due to such conditions, we would have no choice but to term these narrations as Mudh’tarab and disregard them all, especially when Muhammad ibn Yusuf’s contemporaries are all relating 20 raka’ät as we will reveal in detail.

- Abdur-Razzāq is the only narrator who has this wording.

This is another incorrect statement. It is clear stated in his chain that more than one person has narrated this number from Mohammad ibn Yusuf. Abdur-Razzāq himself has mentioned that he reported this account from Däwōd ibn Qays and OTHERS, who have reported it from Muhammad ibn Yusuf.

Some people have tried do defame Abdur-Razzāq by claiming he is a defective reporter because he became blind in his latter years. Consequently he obtained dubious reports from others. They also allege that it is uncertain whether this particular report has been narrated before or after his confusion therefore it cannot be accepted.

It is true that Abdur Razzäq became blind in old age however this happened long after he compiled his book Al Musannaf. The hadëth we are currently debating is recorded in this very compilation. Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, the famous imam of fiqh and a student of Abdur-Razzäq pointed out, “Whoever heard [a hadëth] from the book(s) of Abdur Razzäq then that [narration] is the most accurate.”

In conclusion this particular hadëth is authentic but it cannot be used as evidence; not because of the unwarranted criticism aimed at Abdur Razzäq by certain individuals, but rather due to the irreconcilable numbers reported by Muhammad ibn Yusuf which have made his reports problematic and unreliable.

Interestingly Imam Mälik himself does not practice the narration of 11 raka’ät even though he is the very one who related it from Muhammad ibn Yusuf. He rather claims that the taräwëh prayer is 41 raka’ät!

Sä’ib ibn Yazëd’s second student is Yazëd ibn Khusayfa. His report has been documented and narrated by Ibn Abe Dhi’b, Muhammad ibn Ja’far and Imam Mälik. Their reports are as follows;

4) Ibn Abe Dhi’b reported from Yazëd ibn Khusayfa, who reported from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd who said, “People would stand in [prayer] during ‘Umar ibn Khattāb’s رضى الله عنه time in the month of Ramaźhän for twenty raka’ät.” He also added, “They would recite [suras that consist of] 100 verses and lean on their canes in the days of ‘Uthmän ibn ‘Affän رضى الله عنه due to the intensity of the prayer.” [Sunan Al Bayhaqë: 4617]

5) Muhammad ibn Ja’far narrated, “Yazëd ibn Khusayfa reported to me from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd who said, “We would stand [in taräwëh] during the time of ‘Umar ibn Khattäb for twenty raka’ät with witr’.” [Ma’rifat Al Sunan wa Al Aathär, Bayhaqë]

6) Ibn Hajar said, “Imam Mälik narrated through a transmission chain that leads to Yazëd ibn Khusayfa who reported twenty raka’ät from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd. [Fat’h Al Bari]

Upon observing these narrations one will notice that all of Yazëd ibn Khusayfa’s reports are consistent in reporting twenty raka’ät unlike the inconsistent numbers narrated by Muhammad ibn Yusuf. However some people have stepped forth to criticize Yazëd ibn Khusayfa after doing a ‘comprehensive background check’ on him and have thus uncovered several elements of weakness in him. They are;

- Imam Ahmad has pointed out that Ibn Khusayfa’s reporting is ‘Munkar’.

Before debating this point let’s just take a look at what has been written about Yazëd in the books of ‘Rijaal’. Imam Mazzi has written the following about Yazëd in Tah’dhëb Al Kamäl;

- Abu Bakr ibn Athram reported from Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Abu Hātim and Nasa’ië (that Yazëd is) trustworthy.

- Abu Ubaidullah Al Aajuri reported from Abu Däwōd that Imam Ahmad said, “Yazëd is a Munkir Al Hadëth.”

- Ahmad ibn Sa’d ibn Abu Maryam reported from Yaĥyä ibn Ma’een that Yazëd is trustworthy and an authority.

- Muhammad ibn Sa’d said, “Yazëd was a worshipper, an ascetic, a frequent reporter of hadëth and was trustworthy.”

From this information we learn that a total of 5 scholars have authenticated Yazëd and have labeled him as trustworthy. They are;

- Ahmad ibn Hanbal

2. Abu Hātim

3. Imam Nasa’ië

4. Yaĥyä ibn Ma’een

5. Muhammad ibn Sa’d

On the other hand only one person has criticized him; Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal. His criticism contradicts the authentication he has issued along with other great scholars. It is based on this that Dr. Bashār ‘Awād Ma’ruf has written, “This [criticism] is not confirmed from Ahmad.”

He further writes “In ‘Elal (a book written by Imam Ahmad’s son) Abdullah has stated [about Yazëd ibn Khusayfa], “I only know good things about him,” and this is clear authentication!”

In conclusion Yazëd ibn Khusayfa is a trustworthy, authentic narrator. The criticism aimed at him by Imam Ahmad is to be discarded, especially when he is one of the many scholars who have authenticated him. Consequently Yazëd’s report will not be rejected but rather it will be accepted and shall serve as a strong piece of evidence.

Some people have argued that Ibn Khusayfa’s report is Shādh [2] because Muhammad ibn Yusuf is a stronger narrator than him. Häfiżh Ibn Hajar has described Muhammad as trustworthy and meticulous while he has only described Ibn Khusayfa as trustworthy. Now because Ibn Khusayfa’s report of twenty does not coincide with Muhammad ibn Yusuf’s report of eleven it shall be considered unreliable.

By studying the works of Häfiżh ibn Hajar we find the total opposite of what has been alleged. The following statements are found about each individual in Häfiżh’s famous work, Tah’dhëb Al-Tah’dhëb, an abridged version of Imam Mazzi’s Tah’dhëb Al Kamäl;

Muhammad ibn Yusuf

- Yaĥyä ibn Sa’ëd said, “Muhammad ibn Yusuf is more trustworthy than Abdur Rahmän ibn Hamëd and Abdur Rahmän ibn ‘Ammär. He was lame and a writer.”

- Sadaqa ibn Faźhl said, “Yaĥyä ibn Sa’ëd used to praise him and give him preference over Muhammad ibn Abu Yaĥyä.”

- Bukhäri said, “Yaĥyä ibn Sa’ëd was like him.”

- Ibn Ma’een said, “Yaĥyä told me, ‘I have not seen any shaykh resemble him in reliability’.”

- Ibn Ma’een, Ahmad and Nasa’ië said, “[He is] trustworthy.”

- Mus’ab Al Zubairë said, “He was a noble man and he came to Madina.”

- Ibn Hibbān has mentioned him in [his book] Al Thiqät.

I (Ibn Hajar) say, “Ibn Madënë said, “Muhammad ibn Yusuf, the lame is trustworthy,” and Ibn Shä’hën mentioned in Al Thiqät, “Ahmad ibn Sälih (the Egyptian) said, ‘He is a man of great importance.” He (also) said, “Ahmad ibn Sälih was amazed by him.” [p. 342 vol. 5, Dar Ihyä Al Turäth Al Arabi 1993]

Yazëd ibn Abdullah ibn Khusayfa

- Athram reported from Ahmad, Abu Hātim and Nasa’i that he is trustworthy.

- Al Aajuri reported from Abu Däwōd that Ahmad mentioned, “He is Munkir Al Hadëth,” (this point has already been discussed).

- Ibn Abi Maryam reported from Ibn Ma’een that he is trustworthy and an authority.

- Ibn Sa’d said, “He was a worshipper, an ascetic, a frequent reporter of hadëth and was trustworthy.

- Ibn Hibbān has listed him in [his book] Al Thiqät.

I (Ibn Hajar) say, “Ibn Abdul Barr declared, “He was the nephew of Sä’ib ibn Yazëd and was trustworthy and reliable’.” [p. 214 vol. 6, Dar Ihyä Al Turäth Al Arabi 1993]

These two extracts clearly show that the only words of authentication used for Muhammad ibn Yusuf are ‘trustworthy and reliable’, while for Yazëd words such as trustworthy, reliable and authority have been used thus making Yazëd a stronger narrator than Ibn Yusuf according to the rules of hadëth. Likewise there is no mention anywhere in these two extracts of Ibn Hajar calling Ibn Yusuf ‘meticulous’.

Another ‘element of weakness’ allegedly found in Ibn Khusayfa is that he is not as knowledgeable of Sä’ib ibn Yazëd’s reports as Muhammad ibn Yusuf because Muhammad ibn Yusuf was Sä’ib’s nephew unlike Ibn Khusayfa. Firstly, according to the rules of hadëth relationship does not enhance a reporter’s authenticity nor does it imply that he is more knowledgeable of his relative’s reports than others. Secondly, if by chance relationship was a factor that enhanced a person’s knowledge and reliability then Muhammad ibn Yusuf would not be any more knowledgeable than Yazëd because he too was Sä’ib’s nephew as has been mentioned in the above extract. In conclusion there are really no elements of weakness found in Ibn Khusayfa at all due to which his reports should be discredited.

The third student of Sä’ib ibn Yazëd is Härith ibn Abdur Rahman ibn Abu Dhubäb, whose reports are as follows;

7) Ibn Abdul Barr related, “Härith ibn Abdur Rahman ibn Abu Dhubäb reported from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd that the [night] prayer [in Ramaźhän] during ‘Umar’s رضى الله عنه era was 23 raka’ät.” Ibn Abdul Barr then explained, “The [additional] three are considered to be the witr prayer.”

8) Abdur Razzäq recorded in his Al Musannaf from Aslami, who reported from Härith ibn Abdur Rahman ibn Abi Dhubäb, who reported from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd, “We would finish the prayer close to the rise of dawn. The prayer during ‘Umar’s رضى الله عنه era was 23 raka’ät. [Hadëth no. 7733]

These two reports coincide with the authentic and consistent reports of Ibn Khusayfa above. Here Härith has reported 20 raka’ät from Sä’ib ibn Yazëd with an additional 3 raka’ät for witr just as his contemporary, Ibn Khusayfa. This leads us to the conclusion that the correct number reported by Sä’ib is twenty and not eleven.

Some people have labeled these reports as weak due to Ibn Abu Dhubäb allegedly having a poor memory. The truth is that mixed opinions have been expressed by various scholars about his authenticity. Häfiżh ibn Hajar writes in Al Tah’dhëb;

- Ibn Ma’een said, “He is renowned.”

- Abu Hātim mentioned, “Darāwardi reported ‘Munkar’ narrations from him. He is not strong.”

- Abu Zur’ah said “He is unobjectionable.”

I [Ibn Hajar] say Ibn Hibbän has listed him in Al Thiqät and has written, “He is from the accurate ones and passed away in the year 146 H…”

This clearly shows that Häfiżh Ibn Hajar considered Ibn Abu Dhubäb to be a trustworthy and authentic narrator, for he has based his verdict on Ibn Hibbän’s authentication. Therefore his narration of twenty raka’ät can be used as a reliable source. Even if one were to declare his narration weak, it would still be considered reliable due to it coinciding with the authentic and precise reports of Ibn Khusayfa. According to the principles of hadëth, if a weak report is supported by an authentic report, as is the case here, then the weak report would be upgraded to being reliable and would thus be categorized as ‘Hasan le Ghairihi’.

The people further argue that the status of the other narrators in the transmission chain is not known because Ibn Abdul Barr’s book in inaccessible today. Through this argument they are indirectly contending that this hadëth is unreliable because of this very factor. It is true that Ibn Abdul Barr’s book is not accessible however this very hadëth is found in Abdur Razzäq’s Al Musannaf with the following narrators;

1) Abdur Razzäq: An authentic narrator as we have discussed in great detail.

2) Ibrähëm ibn Muhammad ibn Abi ibn Yaĥyä Al Aslami: This is a heavily criticized reporter due to some controversial beliefs he held. An interesting point to note though is that despite his corrupt beliefs some great scholars have considered him to be a trustworthy narrator of hadëths, such as Imam Shäfi’ë. Imam Mazzee has written in Tah’dhëb Al Kamäl, “Rabë’ ibn Sulaimän said, “I heard Imam Shäfi’ë say, “Ibrähëm ibn Abi Yaĥyä was a Qadari.[3]”

Rabë’ was then asked, “Then what caused Imam Shäfi’ë to narrate [hadëths] from him?”

He replied, “He used to say, ‘I would prefer that Ibrähëm fall from a distant place rather than him resorting to lying. He was TRUSTWORTHY in hadëth!’”

Abu Ahmad ibn ‘Adë said, “I asked Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Sa’ëd, “Do you know anyone who has praised Ibrähëm ibn Abi Yaĥyä apart from Imam Shäfi’ë?’”

He replied, “Yes. Ahmad ibn Yaĥyä Al ‘Awdi told me that he heard Hamdān ibn Asbahāni say when he asked him “Do you embrace the narrations of Ibrähëm ibn Abi Yaĥyä?”

He replied, “Yes.”

Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Sa’ëd then told me, “I studied the hadëths of Ibrähëm ibn Yaĥyä extensively and [it turned out that] he is not a ‘Munkir Al Hadëth’.”

Abu Ahmad ibn ‘Adë further said, “This statement is precisely correct for indeed I myself have also studied many of his narrations and I did not find any of them to be unreliable except for those that were narrated from questionable shaykhs.”

In conclusion Ibrähëm ibn Muhammad ibn Abi Yaĥyä’s narration here is reliable especially when it is coinciding with the authentic narrations of Ibn Khusayfa.

3) Härith ibn Abdur Rahman ibn Abi Dhubäb

4) Sä’ib ibn Yazëd

All these narrators are trustworthy. Thus this hadëth will also be considered reliable.

Another hadëth on ‘Umar’s رضى الله عنه practice is;

9) Mälik reported from Yazëd ibn Rōmān who said, “People would stand (in prayer) during the time of ‘Umar ibn Khattäb in the month of Ramaźhän for twenty-three raka’ät.” [Al Mu’atta: 250]

Some people have labeled this hadëth weak due to it being Mursal[4]. Although this hadëth is Mursal it does not necessarily imply that it is weak. The reason behind this is that hadëth scholars in the past have held mixed views regarding its authenticity. Shaykh Muhammad Jamäluddën has written in his book Qawä’id Al Tahdëth (The Rules of Narrating) that scholars are split into three groups on this issue;

1) Some scholars consider all such narrations weak and unauthentic.

2) Some scholars claim that all such narrations are authentic. This is the view of Imam Abu Hanëfa, Imam Mälik, Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Ib